Not Just Autism: The Deeper Architecture of H. divergens Minds

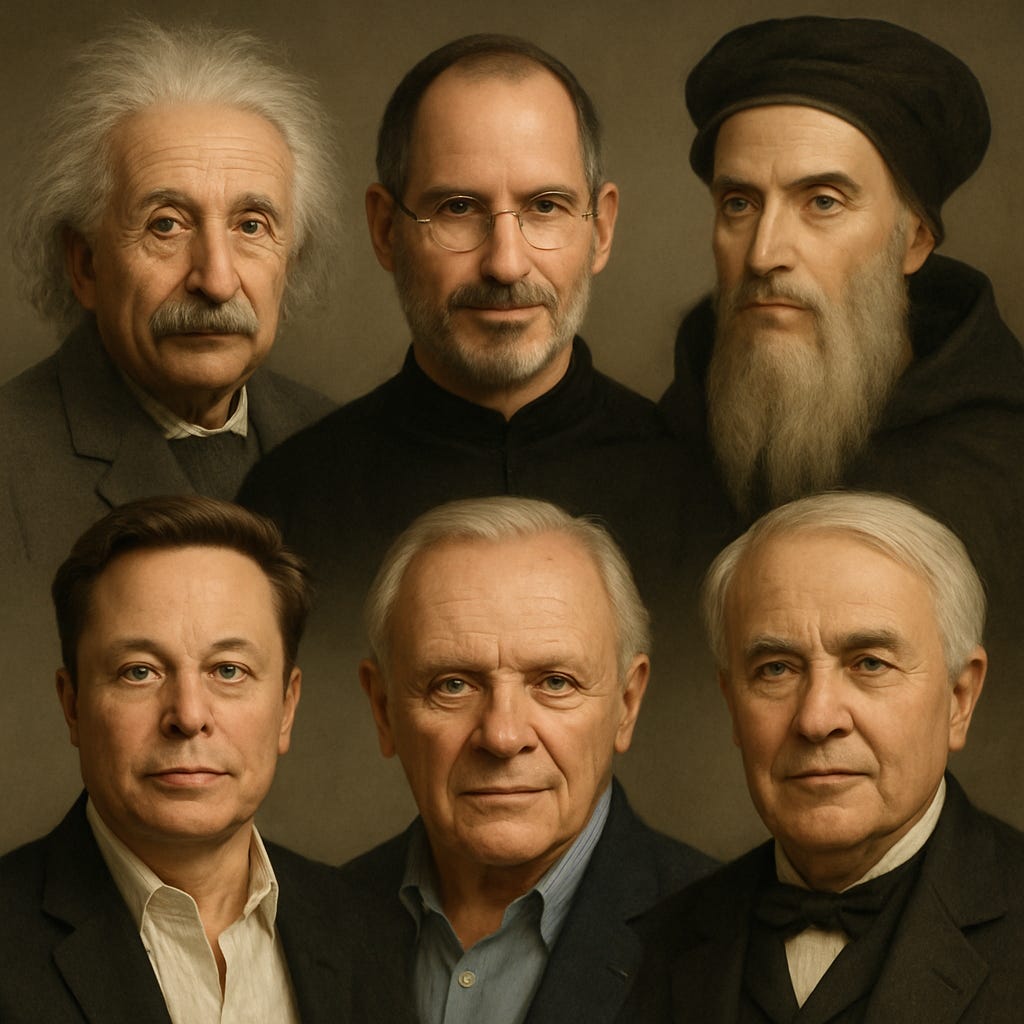

What Einstein, Leonardo, Aquinas, Jobs, Musk, Hopkins, and Edison teach us about Homo divergens beyond autism.

The idea that there might be more than one kind of human mind has been suggested for centuries, usually by poets and mystics rather than scientists. Every society notices that some individuals think in neurodivergent ways that do not match the neurotypical model of human cognition. They build intricate worlds in their heads, move through life with unusual attention patterns, or pursue ideas that seem detached from the ordinary concerns of the surrounding culture. In the Homo Divergens Project, my work on this emerging concept, I use the term to describe individuals whose minds operate in this pattern-seeking, system-building, internally driven mode. Over time, readers of my Substack have asked whether this H. divergens profile is simply another way of talking about Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The short answer is no. The more interesting answer requires us to look carefully at what the two patterns share and where they part company.

To explore this question, I conducted a preliminary meta-analysis of seven iconic figures. The list includes Albert Einstein, Steve Jobs, Thomas Aquinas, Leonardo da Vinci, Elon Musk, Anthony Hopkins, and Thomas Edison. These individuals were chosen not because they fit any single mold but because there is a substantial public and biographical record on them. That record allows us to infer cognitive style in a cautious, historiometric way by examining the documented traits of their thinking, their emotional lives, their social behavior, and the form their creativity took. This exercise does not produce diagnoses of any kind. Instead, it gives us a comparative window into how H. divergens style and autism style might overlap in some individuals and diverge sharply in others.

In the seven figures, the clearest pattern is the presence of a systemizing mind. Systemizing refers to the ability and preference for understanding the world in terms of rules, structures, and principles. It often includes a drive to identify patterns that are consistent across different domains. Every person in this group demonstrates high or extremely high levels of systemizing behavior. Einstein lived in abstract systems of mathematical relations. Aquinas built a huge theological architecture (over 10 million words in English translation) that operated like a conceptual cathedral. Leonardo found patterns in human anatomy, fluid mechanics, optics, and geology. Even artistic or entrepreneurial members of the group, like Hopkins and Jobs, show an underlying tendency to think in structures. Jobs famously insisted on coherent aesthetic systems rather than isolated features. Hopkins speaks often about the architecture of a character and the internal logic he must inhabit in order to portray it convincingly. This universal pattern across the sample shows that systemizing is a core component of the H. divergens profile.

“I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.”

Einstein, A. (1952). Ideas and Opinions. New York: Crown Publishing. Originally attributed to a 1952 interview and later included in Ideas and Opinions.

The presence of strong systemizing does not automatically indicate autism, but it is true that systemizing often appears in autistic cognition. In fact, modern research suggests that systemizing is one of the strongest cognitive predictors of autism-related traits. The difference lies in what comes with the systemizing.

In Baron-Cohen’s research (2009), “systemizers” are individuals who have a strong drive to analyze or construct systems to understand how they work by identifying patterns and rules. This is a key component of his empathizing-systemizing (E-S) theory of autism, which suggests that autistic people are “hyper-systemizers” with an exceptional ability to systemize, coupled with deficits in empathizing. The theory also proposes that within the general population, systemizing is more prevalent in males, while empathizing is more prevalent in females.

In my Micro 16 Framework, systemizing is only one part of a wider profile that also includes imagination, emotional depth, world building, and a form of internal drive that does not map cleanly onto the autism spectrum. In other words, many autistic individuals are systemizers, but many systemizers are not autistic. Systemizing is necessary for H. divergens style, but not sufficient to classify someone as autistic.

A second pattern that appears in the group is monotropic focus, which refers to a cognitive style that concentrates attention on one subject or project with unusual intensity. This deep focus is often associated with flow states and highly productive bursts of work. The degree of monotropism varied in my small sample of individuals and turns out to be one of the most revealing differences between H. divergens and autism. Einstein, Musk, and Hopkins all display strong monotropism, often to the point of narrowing their immediate awareness of the environment. For example, biographers describe Einstein becoming so absorbed in his internal world that he forgot appointments and social obligations. Musk describes childhood states of total internal preoccupation, and Hopkins has spoken about the intense narrowing of attention he experiences when building a role.

“Learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

Leonardo da Vinci, Notebooks. Commonly cited from the Codex Atlanticus; widely attributed and included in multiple editions of The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, ed. Richter, 1888.

Others in the group were different. Leonardo was undoubtedly capable of deep immersion, yet his mind moved fluidly across domains rather than settling permanently into one. He could spend days studying the structure of bird wings, then shift abruptly to painting, military engineering, anatomy, or hydraulics. His attention was intense but switched across multiple domains. Jobs possessed a similar switching mind. He could obsess over a design problem for a period of time, but he also moved rapidly between engineering, marketing, management, and aesthetic concerns. This variation within the group suggests that monotropism intensifies H. divergens traits but does not define them. When monotropism is combined with high systemizing and unusual social signaling, ASD adjacency becomes more likely. When monotropism is weaker or more fluid, the H. divergens expression tends to take a more polymathic or integrative form.

Social signaling is the next important pattern, and it is the one most strongly associated with ASD adjacency in this small sample. Social signaling refers to the subtle nonverbal and verbal cues that people use to indicate attention, emotional state, relational warmth, or social alignment. Neurodivergent individuals often have their own style of signaling, which can be misinterpreted by others. In autism, the difficulty with social signaling is typically more pronounced. This difference becomes clear when we compare the seven figures. Einstein was known for blunt communication and physical awkwardness. Musk displays a flat affect and an unconventional online communication style. Hopkins has long described himself as socially awkward and has considered the possibility of being on the spectrum.

By contrast, Leonardo functioned comfortably with patrons, apprentices, and elites. Jobs was famously abrasive, but he also had a powerful charismatic mode that he could deploy in public settings. Aquinas seems to have been quiet and reserved, but he functioned effectively within the scholastic and ecclesial world. Edison was brusque and absorbed in his work, yet he operated competently within industrial and collaborative environments. These differences show that social signaling is the marker that most strongly separates H. divergens from autism. If someone combines high systemizing, strong monotropism, and consistently atypical social signals, the probability of ASD adjacency rises. If only one or two of those traits are present, the likelihood diminishes.

Other H. divergens markers do not map closely to autism at all. Creativity and world building fall into this category. These refer to the ability to generate new conceptual spaces, narratives, designs, theories, or inventions. All seven individuals display high levels of creativity and world building, but this does not correlate with ASD adjacency. Leonardo and Jobs are the clearest examples. Both are H. divergens exemplars in terms of creativity, but neither shows strong ASD-like patterns in social behavior or sensorial rigidities. Aquinas expresses his world building in theological terms, creating a conceptual structure that mirrors the architectural cathedrals of his time. Thomas Edison built industrial systems and practical inventions at an unprecedented pace. Edison and his team tested over 6,000 different materials for light bulb filaments, though he also famously stated he tried 3,000 different theories in his work. Yet creativity, on its own, tells us nothing about ASD probability. It is a general H. divergens trait, not an autism-specific one.

Emotional intensity and noetic orientation behave similarly. Emotional intensity refers to the strength and complexity of emotional experience, while noetic orientation refers to a cognitive style focused on meaning, spirituality, or deep reflection. These traits appear across the H. divergens profiles but do not predict ASD adjacency. Hopkins, for example, displays emotional depth and introspection, yet his ASD adjacency stems mainly from social signaling and attention patterns. Aquinas had extreme noetic orientation, but there is little in the record to suggest autistic cognition. Jobs had high emotional reactivity without significant sensory rigidity. Elon Musk displays emotional variability, but again, those traits do not align neatly with autism. This suggests that H. divergens cognition integrates emotional and spiritual dimensions in ways that are not accounted for in autism frameworks.

The assessment of sensory atypicality is more complex. Sensory atypicality is a neurological difference in how the brain processes and responds to sensory information from the environment, including sounds, sights, smells, tastes, textures, and body awareness. It can manifest as being overresponsive (hyper-sensitive), underresponsive (hypo-sensitive), or seeking more intense sensory input than others. This can lead to challenges in everyday life and is often associated with neurodevelopmental conditions like autism. Sensory atypicality appears often in neurodivergent individuals, yet historical data on sensory processing are sparse and ambiguous. Edison’s hearing loss complicates interpretation. Leonardo’s emphasis on sensory detail may reflect artistic mastery rather than neurological sensitivity. Einstein and Musk have some documented sensory preferences and rigidities, but the evidence is inconsistent. Without reliable sensory data, this marker cannot serve as a strong predictor unless supported by other ASD-consistent traits such as social signaling differences and monotropism.

“I am very unsocial. I find it hard to talk to people. I think I am a bit Asperger’s.”

Hopkins, A., quoted in The Telegraph, interview by Martyn Palmer, 2014.

Also cited in subsequent interviews where Hopkins discusses autistic traits.

Taken together, these patterns form a preliminary map of the overlap between H. divergens and ASD cognitive styles. H. divergens appears to require systemizing, creativity, internal drive, and a tendency toward world building. Autism adjacency appears when systemizing is combined with strong monotropism and atypical social signaling. In this small sample, the overlap occurs most clearly in Einstein, Musk, and Hopkins. They exhibit systemizing cognition, deep focus, and social atypicality to a degree that supports ASD adjacency. Yet even within this group, H. divergens offers additional explanatory value. Einstein’s political and moral engagement, Musk’s long horizon civilizational goals, and Hopkins’s reflective emotional depth all extend beyond the traditional autism framework.

For the others, H. divergens provides a comprehensive description of cognitive style, while autism does not. Leonardo’s polymathic movement across domains, Jobs’ seamless blending of engineering and aesthetics, Aquinas’s theological architecture, and Edison’s industrial innovation all illustrate H. divergens patterns without implying ASD. These minds are not defined by monotropic fixation or social signaling difficulties. Their H. divergens traits express themselves through creativity, world building, moral independence, and cross domain integration. These traits are not central to autism and often sit outside the formal scope of autism research.

This raises an important question for the broader H. divergens project. If autism is not the defining feature of H. divergens cognition, what is the relationship between the two? The evidence suggests that autism represents one pathway into H. divergens style, particularly when certain traits cluster together. Another pathway may involve polymathic integration, where the individual has a wide bandwidth of attention rather than a narrow one. A third pathway might involve emotional or spiritual depth, which can steer cognition toward introspection, theological synthesis, or artistic world building. H. divergens, in this sense, is a family of cognitive styles rather than a single type.

This preliminary analysis of seven historical and public figures does not settle the matter, but it brings the contours of the Project’s landscape into sharper focus. H. divergens cognition is broader, richer, and more varied than autism alone. Autism represents a subset where specific combinations of attention, social signaling, and sensory processing align with H. divergens traits. But H. divergens also lives in Leonardo’s notebooks, in Aquinas’s doctrinal architecture, in Jobs’ product vision, and in Edison’s laboratories. It reaches into the imaginative, the moral, the artistic, and the noetic dimensions of human life that autism research does not address directly.

In future work, my aim is to map this cognitive landscape more clearly, using the Micro 16 markers as the structural framework for identifying patterns that cut across time, culture, and domain of expertise. My hope is not to divide humanity into new categories, but to understand the diversity of human cognition at a deeper level. If we can articulate the structure of H. divergens style with precision, we may gain new insight into human evolution and its creativity, innovation, social difference, and the ways individuals shape the world through the unique architecture of their minds.